Finally ready to switch your dial from “auto” to that “M” on your camera? First, let’s make sure you understand what you’ll need to adjust to get the shot you’ve been wanting to take! In this article, we’ll talk about setting exposure properly, what happens when adjusting your shutter speed, ISO, and aperture, and some other helpful information that comes with these settings. Understanding and utilizing more features offered by a professional or prosumer quality camera will only give you more tools to express your artistic vision.

What is Shutter Speed?

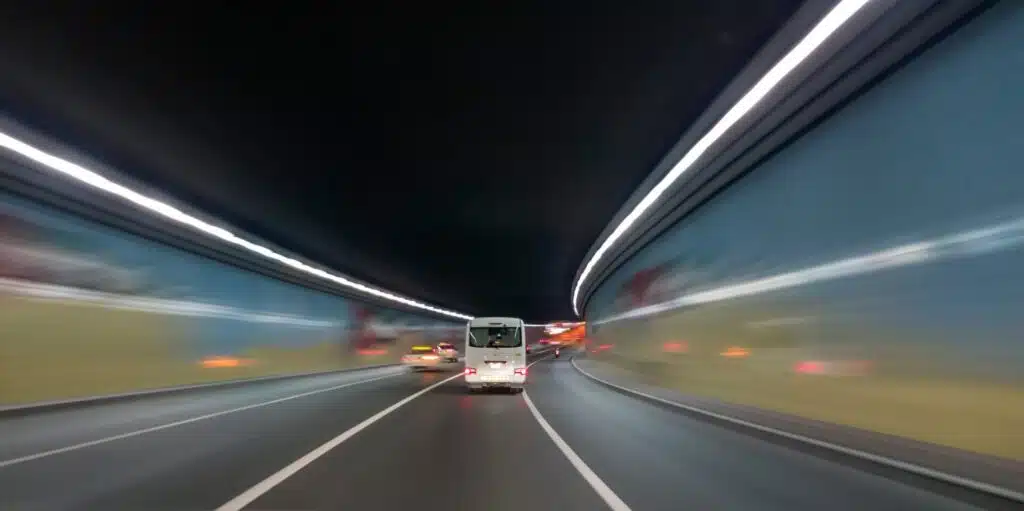

Let’s jump right in! Shutter speed is one of the more straightforward concepts to understand because it explains itself. Shutter speed is the time the shutter stays open every time you take a photo. The longer your shutter stays open, the more light your camera sensor is exposed to. One of the primary uses of shutter speed is to show motion or, adversely, lack of movement. When shooting a standard portrait or headshot, you typically want a pretty sharp image with little to no motion. Whereas if you’re shooting a moving vehicle, you may want to have a panning shot in which the car is sharp against a blurry background, creating the impression of speed and direction. You would typically achieve this with a faster shutter speed for the portrait and a slower shutter speed for the car shot. While adjusting your shutter speed, as you decrease the time the shutter stays open, you will reduce the amount of light that can reach your camera sensor. If you can’t add light, you’ll have to adjust other settings.

Aperture

Aperture is the next easiest concept to understand regarding manual settings. Aperture, or “f-stop” is the opening within your lens that allows light to pass through. There are usually a few sets of numbers printed on the outside of a lens that helps you understand what that particular lens can do for you. For example, let’s say you have a lens that says 100-400mm f/5.6-6.3 ø67; what does this mean?

• 100-400mm: this is the focal length of the lens. This tells you how wide or how narrow of a field of view you will have.

• f/5.6-6.3: This is your aperture (this number can be two different numbers, a single number, it can be prefaced by a “1:”, etc.). This tells you the widest aperture that is available for that lens. If it is a prime lens or fixed-focal-length lens, it will have one number, like f/5.6. If it is a zoom lens it could have a range. For example, at 100mm, your widest aperture is f/5.6, and if you keep zooming in, it will eventually switch to f/6.3.

• Ø67: this simply tells you what size filter or lens hood will fit on your lens.

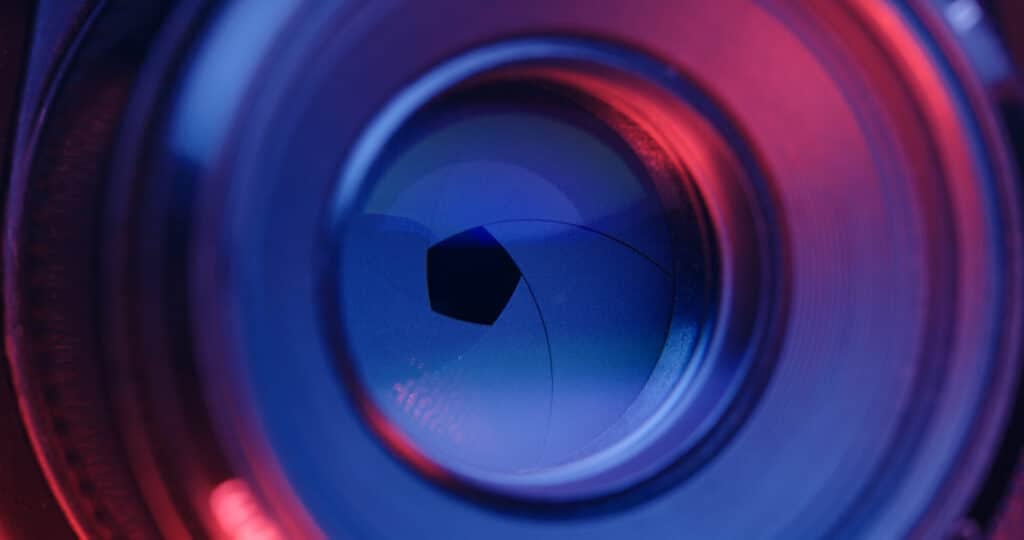

Lenses have blades arranged one on top of another in a circular pattern that opens and closes to create an opening for light to pass through. This is called the aperture diaphragm. The lower the number (f/1.8), the wider the opening; the higher the number (f/22), the smaller the opening. One of the main uses of aperture is to create depth or clarity in photos. By setting the aperture appropriately, you can draw focus (literally and metaphorically) to anywhere you want within your image. One of the most common beginner mistakes in photography is always shooting with a wide-open aperture (i.e., f/1.8). While this produces a pretty, buttery smooth background blur or bokeh, it doesn’t always work for what you’re shooting.

One of the main reasons to adjust your aperture is to determine how much of your subject you want in focus. For example, if you are shooting a portrait, it’s common to have their eyes be the focal point and for focus to start dropping off around the ears; let’s say that’s somewhere around f/4. If you were shooting that same portrait but wanted more o the background in focus, you would have to increase the number of your aperture or “stop down,” let’s say to around f/8, which closes your aperture diaphragm and allows you to increase the amount of your image that is in focus. It’s important to note that distance between objects also influences the amount of blur or bokeh. While further away (i.e., a 400 mm lens at f/6.3), a higher aperture can have a similar effect as a lens set to a lower aperture at a close distance (i.e., an 85 mm lens at f/3.2). Once you learn what kind of shot you want, you can adjust your other settings to help you achieve what you’re looking to create.

ISO

One of the more difficult concepts to explain and visualize is ISO. ISO is how you set your camera’s sensitivity to light. Settings usually start as a base of ISO 100 and double for each setting up to whatever range that is set for your camera body. Say you’re shooting a portrait, and your camera is set to f/3.2, shutter speed 1/80, and ISO 100, but it’s still just too dark. You don’t want to lower your aperture to let in more light because you don’t want parts of your subject to fall out of focus. You don’t want to lower your shutter speed because your subject is moving slightly, and you want a sharp image without any motion blur. If you can’t add more light to your subject, your only recourse is to increase the ISO. The general rule of thumb here is to try and shoot at as low of an ISO as you can. Increased ISO tends to result in noisy (or grainy) images. Something to note is that some cameras have extended ISO ranges that are processed within the camera. It could have desirable or undesirable results and should be used as a tool only when needed.

What does it mean when cameras have shutter speed, aperture, or ISO priority modes? This is a way to make your life easier. Priority modes allow you to adjust one setting while letting the camera automatically adjust the other settings. In aperture priority, you can adjust only the aperture, while the camera will change your shutter speed and ISO to expose the image properly. The other modes follow suit; in ISO priority, you adjust ISO manually, and in shutter speed priority, you adjust shutter speed manually. If you know you won’t have enough time to change each setting, it could be a good idea to use one of these modes. Say you’re shooting an event, and you know you need a fast shutter speed because the subject is in motion, but you don’t have time to think about the other settings. Shutter speed priority will enable you to only adjust shutter speed and still end up with properly exposed images. You won’t necessarily use these all the time, but it’s good to know what they are, just in case you need them.

Practice Makes Perfect

It takes time and practice for these concepts to become second nature. Every shooting scenario is unique and requires a different combination of settings to produce the desired result. The best way to understand what your gear is going to do in different scenarios is to make a point of shooting every day. Shoot everyday objects: a fast-moving ceiling fan, a static vase, or a car driving by. Practice shooting in brightly lit environments and poorly lit environments. Think about what conditions you might encounter in the real world and try to simulate those in a controlled environment where the consequences of failure are minimal.

Once you’ve mastered exposure, you’re off to the races. You’re then free to explore the more interesting worlds of composition, color, shape, character, story, and everything else that goes into creating great art.

Want to take your photography to the next level? F.I.R.S.T. Institute can help with that. F.I.R.S.T. offers hands-on courses designed to equip you with the knowledge and skills you’ll need to succeed in the photography industry. You can learn more about our photography program here.

.

Guest Author

Rainer Schuertzmann

Content Guru - Apex Creative Media